Edmund mbti kişilik türü

Kişilik

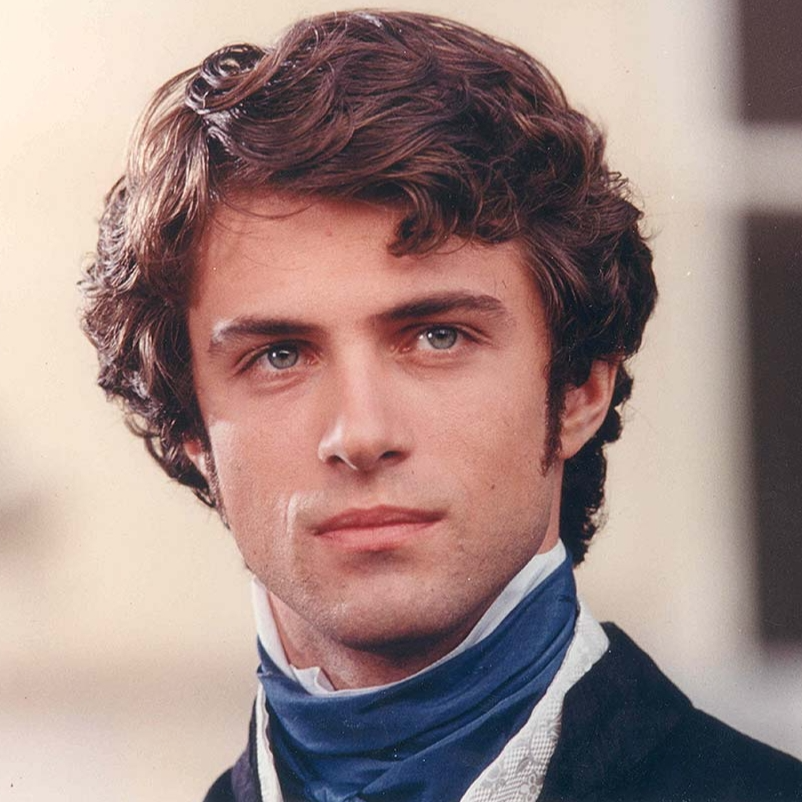

"Edmund hangi kişilik türü? Edmund, MBTI, 3w4 - - 458 'de INTJ kişilik türüdür, RLOEI, RLOEI, büyük 5, ' dır."

He is Shakespeare’s purest nihilist and his prefiguration of Nietzsche. His will and imagination lie so far beyond his earthly surrounds that they are thoroughly cosmic. In all of Edmund’s appearances in ‘King Lear’, he is never truly psychologically immersed in the narrative drama. He is always out, in ‘the cold of interstellar space’, disdaining the tragedy as it unfolds beneath him. This apathy is unwavering throughout the play; a constant even in his final act of mercy which he performs, not out of sincere good will, but because it is a last slight to fate which was supposed to have ordained him a villain; ‘Some good I mean to do, / Despite of mine own nature.’ (Act 5 Scene 3) Lear differs drastically from Edmund in that he is so entirely immersed in the drama, so helpless to his passions and the meddling of the gods, that it is difficult to detect a distinct psyche. In Act 3, he foresees his own descent into madness through rumination on his daughters’ betrayal; ‘When the mind’s free, / The body’s delicate: the tempest in my mind / Doth from my senses take all feeling else / Save what beats there. Filial ingratitude! / Is it not as this mouth should tear this hand / For lifting food to’t? But I will punish home; / No, I will weep no more. In such a night / To shut me out! Pour on; I will endure: / In such a night as this! O Regan, Goneril! / Your old kind father, whose frank heart gave all, / O, that way madness lies; let me shun that; / No more of that.’ (Act 3 Scene 4) Lear’s agitated verse bespeaks his transformation from tyrant to lunatic, which is the central arc of characterisation in the play. Several characters intimate that he was once a beloved, fatherly king, thus further expanding the spectrum of personal development in Lear. Edmund, on the other hand, remains aloof and bitter for the duration of the play due to this cosmic distance from human affairs. This disposition is traceable to the isolating effect of introverted intuition. The Ni progression towards the substrate of immediate phenomena creates a distance between the psyche and its immediate surroundings, which is so evident in Edmund. ‘This is the excellent foppery of the world, that, when we are sick in fortune, often the surfeits of our own behaviour, we make guilty of our disasters the sun, the moon, and the stars; as if we were villains on necessity; fools by heavenly compulsion; knaves, thieves, and treachers by spherical predominance; drunkards, liars, and adulterers by an enforced obedience of planetary influence; and all that we are evil in, by a divine thrusting on. An admirable evasion of whoremaster man, to lay his goatish disposition to the charge of a star. My father compounded with my mother under the dragon’s tail, and my nativity was under Ursa Major, so that it follows I am rough and lecherous. Fut! I should have been that I am, had the maidenliest star in the firmament twinkled on my bastardizing.’ (Act 1 Scene 2) In this famous Nietzschean diatribe Edmund proves that my earlier statement, that he dwells in interstellar space, was certainly a metaphor, since he expresses disdain even for ‘the sun, the moon, and the stars; […] spherical predominance; [and] planetary influence’. With vicious sarcasm he jabs at the characters of the play who attribute their fortune to the stars; ‘An admirable evasion of whoremaster man, to lay his goatish disposition to the charge of a star.’ What are the motions of the planets to Edmund’s indomitable will? He sees behind even these to the fabric of reality itself; ‘Nature’, and ‘she’ is his goddess; ‘Thou, Nature, art my goddess;’ (Act 1 Scene 2) Edmund’s apprehension of images ‘which arise from […] the inherited foundations of the unconscious mind’, is clearly not the perception of an archetypal shell around objective sensations as with Si, but a searching past the extremities of consciousness. The Nature goddess is not particular to a single sensation but common to all of Edmund’s experiences. Jung writes of the Ni-type; ‘His judgment allows him to discern, though often only darkly, that he, as a man and as a totality, is in some way inter-related with his vision, that it is something which cannot just be perceived but which also would fain become the life of the subject.’ In Edmund’s case, the interrelation of the vision with the subject pertains to his moral framework or morality, rather than a representation of data; ‘I should have been that I am, had the maidenliest star in the firmament twinkled on my bastardizing.’ Although it seems that no one disputes that Edmund was a Fi-type, I felt I should provide some justification for that conclusion.

Biyografi

#MagnificentBastard